Blog Published October 8, 2025 · 8 minute read

What If the US Centralized All Federal Infrastructure Financing?

Ryan Norman

The Trump Administration has dismantled key segments of the federal government, making it hard to imagine how the United States will build major infrastructural or energy projects again. Democrats are, rightly, focused on defeating Trump in 2028. Policymakers, however, must consider what kinds of transformative policies may succeed him. The goal cannot simply be for the next generation of Democratic elected officials to restore the pre-Trump status quo. Instead, they must invent newer, better strategies to meet their policy goals and rewire the federal bureaucracy in service of one goal: making life better for the American people.

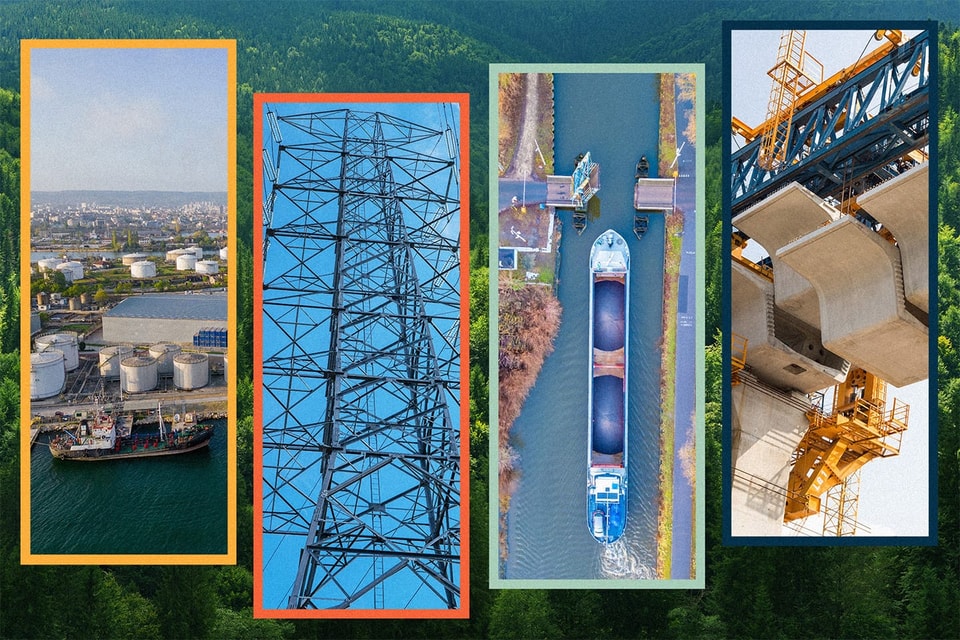

Improving our country’s aging critical infrastructure is central to that goal and rife with opportunity for creative policymaking.

For decades, America has failed to modernize and scale our aging critical infrastructure—particularly for projects that are difficult to finance through private capital alone, such as advanced energy technologies and public infrastructure. Historically, the US has addressed infrastructure challenges through ad-hoc, sector specific reforms that have spawned a range of programs housed within individual federal agencies. Even with recent bipartisan laws like the Energy Act of 2020, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, no modern administration has effectively spurred the sprawling federal government to deliver results more efficiently and quickly.

A strategic long-term federal redesign can position the USG to deliver on its mandate in ways that increase bureaucratic efficiency, share resources (including talent and information), and boost confidence in the federal government as a partner. In doing so, it can tangibly improve life for Americans.

This blog explores what could be possible if the US centralized all federal infrastructure programs into a “National Infrastructure Authority.” This structure could be highly effective in accelerating capital deployment needed to accomplish our national goals, while providing greater autonomy, durability, and long-term direction politically.

The Idea: Establish A Centralized National Infrastructure Authority

The current federal system to support infrastructure development is disjointed. Multiple agencies hold authorities for financing various forms of energy, community and commercial electrical, water, transportation, and telecom infrastructure. This decentralization means that there are broad inconsistencies in departmental approaches to regulations, program mandates, program applications, underwriting principles, tracking and management systems, and organizational culture. Some agencies have been known to periodically share best practices and lessons learned, however this collaboration typically happens on an ad hoc basis, which has not sustained lasting effects. In practice, the current system is that of multiple points of entry—and multiple points of failure–for new project developers. Pain points such as delays between lead and supporting agencies, formal contracting of technical experts from across the federal government, and the need for sign-off from multiple agency heads for parts of the same project make navigating the public bureaucracy fraught.

Imagine instead—a single point of entry. A “full-service shop” conducting business for the entire federal government that could support an infrastructure project across all relevant sectors, sharing information across program teams and with federal agencies, and empowering dealmakers to structure the most strategic use of federal resources. This National Infrastructure Authority (NIA) would be led by a single principal responsible for financing strategy and approving the use of federal capital tools to support new projects.

Further, the Authority could be developed as a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), providing it with the implied credit of the US, as well as the ability to pool capital from private investors. As a GSE, the NIA could be structured with long-term expert leadership, guided by a diverse, well-qualified, and long-term Board of Advisors to maintain the Authority’s alignment with National priorities. This integrated structure could increase the Authority’s long-term financial and political durability, providing increased confidence to public and private investors. This centralization could promote substantial efficiency gains, enable the federal government to look at new projects more holistically (rather than segmenting them into stages fit for each Agency’s jurisdiction), and promote greater certain among public and private investors that the US can be an effective long-term partner.

What Could it Achieve?

Institutional Efficiency

The NIA could enable federal programs to work more effectively and cohesively through streamlined leadership, integrated application processes, consolidation of outreach and compliance activities, underwriting and legal expertise, financial resources, and institutional mandates. These efficiencies could speed the deployment of new critical infrastructure by enabling faster, more comprehensive, and more politically durable investment decisions. Additionally, by looking at these project proposals as a whole, the NIA can better identify gaps in a project’s capital structure and strategically engage executive Departments to pull-in any necessary grant and demonstration that it cannot provide.

Take for an example an applicant seeking to build an energy campus at a new site 25-miles from existing infrastructure: Such applicant might currently seek funding from DOT for the necessary surface transportation needed for the site, financing from DOE to support the construction of the power facility for the campus, as well as funding from EPA to upgrade local water infrastructure necessary to support the project and local community. Through the NIA, the same applicant could work through one front office to structure a single application including all project elements—thereby enabling the Authority to apply a wide range of financing tools to support the project and ensuring a consistent customer experience for all project developers.

Scaled Investments

The NIA could raise significantly more capital for its investments than independent federal programs ever could, due to its ability to issue bonds and draw in private capital. Initially, it could rely on a mix of public and private funding—Congress could continue to provide a baseline of annual support for authorized critical infrastructure programs, especially those supporting higher-risk investments.

As an independent GSE however, the NIA would effectively operate as an infrastructure bank—like successful models in Korea and Canada. The NIA would leverage the implicit support of the USG to issue low-interest bonds, develop sector specific funds, and raise funding from the private sector, domestically and internationally, that could be deployed to support its portfolio projects.

In addition to scaling the resources available, the NIA could be more efficient in capital deployment. The NIA can better leverage public, private, and foreign capital sources in blended arrangements by structuring its capital more flexibly, such as through co-financing arrangements or establishing funds. This could allow investors to address challenges in foreign ownership mandates and provide more confidence to foreign investors (such as Sovereign Wealth Funds) that such investments are secure.

What Could be Downsides?

Redirecting Institutional Inertia

Change will be hard, and building consensus around new structures is not easy. Decades of program operating history, combined with guidance from policymakers on Capitol Hill and across multiple administrations, has shaped the financing programs that exist today. Achieving consensus across the Executive branch and Congress to review, analyze, and streamline authorities would be a significant undertaking.

Further, restructuring would likely require recruiting staff from across the federal government who come from agencies with different risk cultures, authorities, and dispute resolution process, necessitating re-training for teams and building alignment on the NIA’s mission.

In many cases, statutory authorities and funding lines will need to be revised, reauthorized, redirected, and consolidated into a single authorizing committee and appropriations subcommittee, to ensure consistent oversight and Congressional direction. The NIA and its Congressional supporters would need to work together to address these initial programmatic and capitalization barriers.

Concentration of Portfolio Risk

Consolidating financing programs would consolidate financial risks—that would typically be spread across agencies— into a single portfolio, potentially increasing exposure for the federal government. If the NIA were to be developed with additional catalytic tools to fit market gaps (ex. credit, limited equity financing, or insurance authorities), the exposure from a specific investment or applicant could be greater than under the current structures and authorities. However, such risk may be mitigated by establishing a clear risk profile at implementation and reassessing it annually.

Conclusion

If we don’t fix our current system, our growth with be impaired by continued fragmentation of the federal infrastructure financial support ecosystem, and Americans will continue to be faced with sub-standard infrastructure in their communities and a federal government too disaggregated to truly address the problem Without reform, the US government will be a less-effective partner in helping developers and entrepreneurs invest in the United States. We will continue to squander public resources on fragmented, duplicative, and politically unstable systems.

Most of the authorities necessary to make the NIA a reality already exist. With a reimagining and redesign of the executive branch, authorities for existing infrastructure programs at DOE, DOT, USDA, and EPA can be transferred to the new authority, with a structure put in place to formalize coordination with the remaining relevant agencies. This bold restructuring would not only benefit new infrastructure development, but it would allow agencies to focus more explicitly on their core expertise and mission. Cabinet-level agencies would retain mission support capacities for the NIA and continue to implement Administration policy across core USG programs.